Bird Flu Update 2025 –Backyard Flock Keepers’ FAQ’s

Sanshui, a medium sized city in China's southern coastal Guangdong province, is home to the region's Budweiser brewery and its Red Bull factory. More significantly, it is the center of an important agricultural region. In the early spring of 1996, a farmer near Sanshui noticed one of his geese behaving oddly. It appeared sluggish, uncoordinated, and sick. The goose deteriorated quickly and died. Within a matter of hours, other geese in the flock showed similar symptoms. Each one of them also died. Within days, geese, ducks and chickens throughout Guangdong were dying with the same alarming symptoms. It was the beginning of the H5N1 avian influenza outbreak that now covers the planet.

The Guangdong virus spread, mutated and evolved, giving rise to new subtypes. Soon the first human cases appeared—people who caught the infection from their flocks. The virus moved around China with the sale of domestic poultry. Then migratory birds became infected and spread an assortment of H5N1 subtypes around world.

H5N1 first came to U.S. poultry flocks in 2014, causing a severe outbreak. The U.S. ramped up its strict avian flu response—strict biosecurity measures and the “depopulation” of infected flocks. The outbreak was contained in the U.S. and H5N1 disappeared. For a while.

The virus was still alive and mutating into new forms in other parts of the world. In 2020, in the midst of Covid, a tenacious, infectious new H5N1 clade emerged in Asia - 2.3.4.4b. This new H5N1 mutation spread through poultry flocks. Then it found its way to North America.

In 2022, as 2.3.4.4b was ramping up in the U.S., at the request of some folks at the CDC, I wrote a three-part series of articles on bird flu. The information I wrote in those three-year-old articles is still relevant because that bird flu epidemic is still with us! And that’s surprising a lot of people. There have been bird flu outbreaks in U.S. poultry flocks in the past. Animal health officials developed strategies to deal with those outbreaks and they have worked well. Those control measures arrested and eliminated the bird flu outbreaks of 1983, 2004 and 2014.

But this time, the virus is not slowing down. To date (June 2025), in the U.S., over 174 million commercial poultry birds have been culled. Egg prices have increased astronomically. It’s in cats now, and over 80 other mammal species. It’s in dairy herds in many states; thus, it’s in dairy products. 70 people have become infected, and in January of this year, the first human died.

There’s growing concern and lots of questions from backyard poultry keepers. “What, exactly, is bird flu? Are my chickens in danger? How can I protect them? Am I in danger? If I am, how should I protect myself? Why do we keep having new epidemics? Is there something wrong with the way they’re trying to stop it? There’s talk of a new approach to controlling it—how’s that going?

I’ve written this article as an update to my original bird flu series to provide some answers those frequently asked questions.

What is Bird Flu?

You’ve probably had the flu before—fever, aches, and too much daytime TV while you’re stuck on the couch. The virus now killing chickens is a close cousin to the one that made you sick. In fact, all flu viruses—whether they infect humans, pigs, horses, dogs, cats, bats, foxes, skunks, or you name the animal—belong to the same big family: Orthomyxoviridae.

This shared relationship is key to understanding flu. Bird flu, human flu, and all flu—it’s all related. Flu is flu is flu. And sometimes, a flu virus mutates and jumps to a new host species. When that happens, the consequences can be devastating. The new host has no immunity, so the virus spreads rapidly. That’s how pandemics start. In 1918, for example, a bird flu strain jumped to humans, triggering the “Spanish Flu” pandemic, which infected a third of the world’s population and killed an estimated 50 million people.

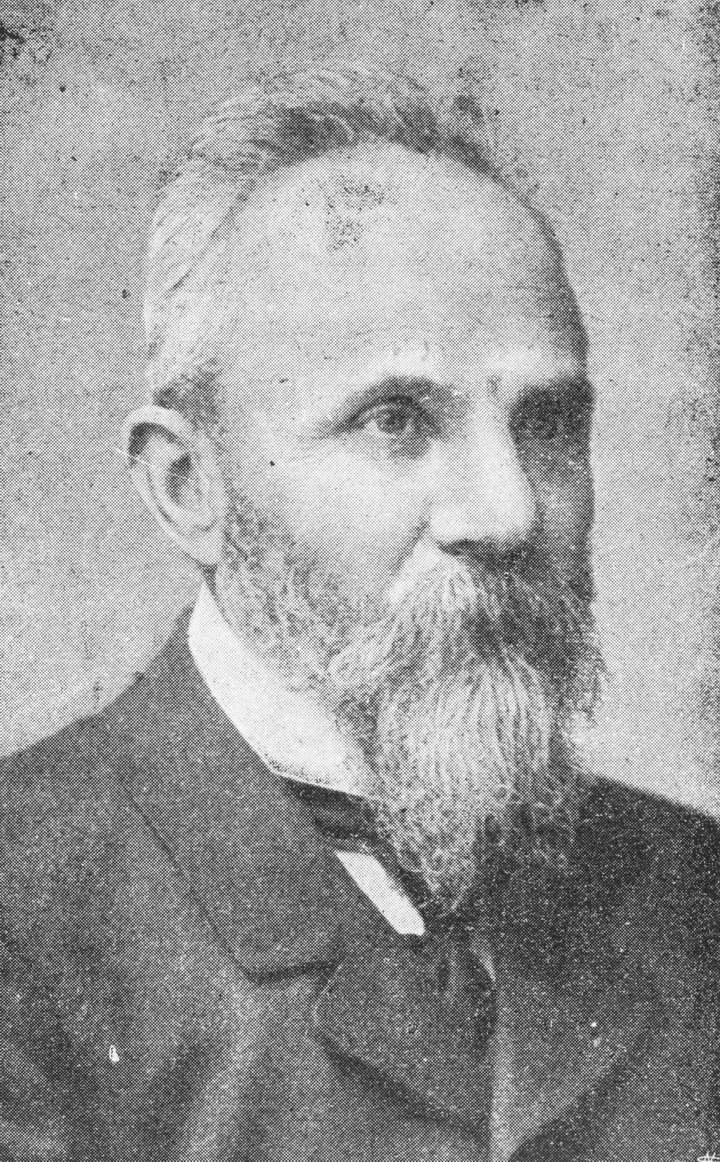

Edoardo Perroncito (public domain)

Bird flu has likely existed for centuries, but we only began to understand it after microbiology emerged as a science. In 1878, Italian veterinarian Edoardo Perroncito described a mysterious disease wiping out poultry flocks. He called it “fowl plague.”

By 1880, microbiologists Sebastiano Rivolta and Pietro Delprato realized this “plague” was actually two different diseases. One was caused by a bacterium we now know as Pasteurella multocida, responsible for fowl cholera. The other one was so small that it passed right through filters that captured bacteria.

Back then, viruses were unknown—but the concept of "contagium vivum fluidum" e.g. “living fluid” was starting to emerge. Scientists discovered that they could spread certain diseases by passing from animal to animal a liquid suspension of tiny unfilterable particles too small to be seen under a microscope. These minute particles would not grow in the laboratory but needed a living host in order to live and reproduce. And thus, viruses were discovered. By 1901, viruses were an established disease agent and fowl plague was recognized as a viral disease.

Once fowl plague had a name and a description, reports of outbreaks came in from across Europe. In 1924–1925, the first U.S. cases were found in New York City’s live bird markets.

By the 1950s, mass bird deaths from fowl plague were being reported globally. In 1957, another human flu pandemic killed over a million people, raising suspicions of a bird-human virus link. When another human pandemic hit in 1968, better lab tools confirmed the connection. In 1981, scientists gathered for the First International Symposium on Avian Influenza and decided that it was time to call fowl plague what it really was: Avian Influenza. Bird Flu.

Today, bird flu viruses are classified as either low-pathogenic (LPAI) or highly pathogenic (HPAI). LPAI strains circulate constantly in wild birds. In backyard flocks, they might go unnoticed or cause only mild symptoms like ruffled feathers or fewer eggs. HPAI is far more dangerous. It spreads fast, causes severe illness, and can wipe out an entire flock. Alarmingly, LPAI can mutate into HPAI.

The current dominant strain—H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b—was first detected in wild birds in the U.S. in the Carolinas in December 2021, and then in Indiana poultry in February 2022. Since then, it has spread across the U.S. It’s one seriously nasty virus.

How Do We Fight Bird Flu?

When bird flu strikes poultry flocks, U.S. animal health experts follow a tried-and-true strategy developed during past outbreaks. This approach has consistently helped contain the disease. There are six main strategies:

Biosecurity: Wild birds are the main carriers of avian flu. To reduce the risk of the virus spreading to poultry, the USDA inspects farms to find and fix potential points of contact with wild birds. They also perform biosecurity audits and often help pay for needed improvements.

Monitoring: To catch outbreaks early, the USDA tests both poultry and wild birds. In 2022, they ran more than 1.8 million tests on poultry and collected nearly 21,000 samples from wild birds.

Quarantine: If bird flu is detected, a control zone is established around the infected site. Movement of poultry and poultry equipment in and out of the area is strictly limited.

Depopulation: All poultry within the control zone are euthanized.

Disinfection: After depopulation, each facility is thoroughly disinfected.

Testing: After disinfection, each facility is rigorously scanned for the presence of the bird flu virus.

This protocol has been the backbone of the U.S. response to avian flu in poultry for decades.

Why Isn’t the Established Strategy Working This Time?

When clade 2.3.4.4b emerged in early 2022, the U.S. already had strong prevention and control measures in place. As always, officials responded swiftly—using surveillance, biosecurity, quarantine, culling, and disinfection. But despite these efforts, the virus kept spreading. Why?

There’s no simple answer. Experts have some ideas, but much of it is still speculation. Here's what might be going wrong:

New Hosts and New Routes of Transmission

Clade 2.3.4.4b is proving unusually adaptable. In the past, avian flu mostly spread through certain migratory waterfowl. Now, this strain is infecting a much wider range of birds, including cormorants, pelicans, vultures, hawks, and falcons. This expansion makes the virus harder to monitor and control.

As University of New South Wales epidemiologist Raina MacIntyre puts it: “We’ve got to think beyond ducks, geese, and swans. They’re still important, but we have to start looking closely at these other species and other routes and think about what new risks that brings.” Many of these new bird hosts show few or no symptoms, which means the virus can spread silently.

The virus isn’t just spreading through birds. It has also jumped to more than 80 species of mammals. The ABC’s of infected mammals include alpacas, bears, and cats, then goes on to include dolphins, elephant seals, fishers, goats, and a whole host of others. You can see the full list here. There is strong evidence of mammal-to-mammal transmission among wild sea mammals such as sea lions, marine otters, porpoises and dolphins. And there is one proven case of direct mammal to mammal spread at a Spanish mink farm where over 50,000 mink were eventually euthanized. Direct mammal-to-mammal spread is alarming because such transmission could bring the virus a step closer to human-to-human transmission and an ensuing pandemic.

Its adaption to new mammal hosts also allows new transmission pathways. For instance, its infection of dairy cows has allowed transmission through milk.

Surveillance Weaknesses

While the USDA offers biosecurity and testing programs for poultry and livestock farms, participation is voluntary. Many farms opt out, leaving large parts of the country essentially unmonitored.

As the virus spreads into cattle, current rules haven’t kept up. Milk testing only started recently. With poor data and gaps in testing, it is likely that officials are underestimating the true scale of the outbreak.

Monitoring wild birds presents an even bigger challenge. Monitoring the virus in one or two wild bird species is challenging. Monitoring it in multiple species is impractical to impossible.

A Slow Response to A Rapidly Changing Virus

Flu viruses are successful because they can evolve and adapt quickly. Government responses typically evolve and adapt glacially. Updating official strategies can take months of bureaucratic review and political debate. By the time a new policy is approved, the virus may have already evolved again. In short: the virus is nimble. The response is not.

Factory Farms

Modern industrial farms cram thousands of animals into confined, often unsanitary spaces. This creates ideal conditions for viruses to mutate and spread.

The Humane League (THL) argued in June 2024 that many livestock diseases could be reduced by moving away from intensive confinement. THL president, veterinarian Vicky Bond, put it bluntly: We’ve created a system “in which thousands of animals are packed into dense, unclean living quarters—creating conditions ripe for disease…The threat remains high unless we collectively change our relationship with nonhuman animals."

Science writer David Quammen echoed the THL statement in this 2024 New York Times essay, calling factory farms “petri dishes for the evolution of novel pathogens.” With so many animals raised in such close quarters, he argued, it's no wonder new viruses are emerging and spreading to humans.

Bottom Line

The old playbook isn’t enough anymore. The virus has changed. The environment has changed. And without stronger surveillance, faster responses, and rethinking how we raise animals, avian flu may continue to outpace our efforts to stop it.

What Is the New “Five Pronged” Strategy to Fight Bird Flu?

In response to the ongoing bird flu crisis, the new administration announced a fresh strategy in early 2025. On February 26, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released a statement titled “USDA Invests Up to $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu and Reduce Egg Prices.” In the release, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins introduced a new five-pronged approach to fight the virus and stabilize the egg market. The five prongs:

1. Strengthen Biosecurity

Expand the Wildlife Biosecurity Assessments Program to poultry farms nationwide since wild birds are the main avian flu vector to domestic poultry. So far, only one of the approximately 150 participating facilities has had an outbreak.

Offer free biosecurity audits to both infected farms and nearby farms. Farms must correct problems to remain eligible for future USDA payouts.

Cover up to 75% of fix-it costs, with a total of $500 million available to help farms address major biosecurity risks.

Send 20 trained epidemiologists to help farms improve defenses against wild bird transmission and bird-to-bird spread.

2. Increase Support for Farmers

Continue compensating farms that must cull flocks due to avian flu infection.

Provide up to $400 million in recovery aid this year to help farms rebuild.

3. Cut Red Tape

Explore ways to scale down depopulation during outbreaks where possible.

Inform consumers and Congress about how regulations affect egg prices, especially in high-cost states like California.

4. Advance Vaccines and Other New Tools

Spend up to $100 million on vaccine research, treatments, and biosurveillance.

Work with global trade partners to minimize export disruptions caused by vaccination, since some countries won’t accept eggs from vaccinated hens.

5. Explore Temporary Trade Options and Global Best Practices

Consider short-term increases in egg imports and reductions in exports to ease prices at home.

Study successful international practices to improve U.S. egg production and food safety.

Will the Five Prongs Stop Bird Flu?

When Secretary Rollins introduced the plan, she acknowledged the challenge ahead. “There’s no silver bullet,” she said, explaining the need for a five-pronged approach. But now, months later, many experts are questioning whether this plan is actually better—or just more of the same, with some serious blind spots.

Where Are the Details?

USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins (public domain)

The February rollout offered only a broad outline. Now, in late June, key details are still missing. How will new testing, audits, and inspections be implemented? What are the timelines? The USDA hasn’t said.

And there’s a bigger problem: staffing. The USDA has lost hundreds of inspectors due to federal cost-cutting, and the Department of Health and Human Services has shed 10,000 workers, including personnel from the FDA’s Veterinary Laboratory Investigation and Response Network—a vital part of the H5N1 testing system. The plan assumes more work with fewer people. That’s a recipe for failure.

Poultry Vaccinations – Not So Easy:

One prong of the new plan suggests avian flu vaccinations for flocks. This strategy is already in place in other countries, and vaccines already exist and are ready to go. The USDA issued a conditional license for avian influenza vaccine to Zoetis in February. Things are definitely moving at warp speed for a chicken vaccine! And vaccinated birds don’t get flu. So, roll up your sleeve and stick out your wing! Problem solved, right?

Well, unfortunately, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

These are “leaky” vaccines, meaning they protect chickens from getting sick, but not from carrying or spreading the virus. Even worse, vaccinated birds test positive in standard flu screenings, making it nearly impossible to detect outbreaks within flocks. Chickens with undetected virus would likely wind up in our food supply. While cooking kills the virus, what consumer will want to buy chickens that may be infected with bird flu? Certainly not the consumers in many of the countries we trade with—which is why many countries have bans against importing meat from countries that vaccinate poultry.

Vaccination could also backfire by creating silent reservoirs of the virus, giving it more opportunities to mutate and possibly become more dangerous.

There’s also a divide within the poultry industry:

Egg producers support vaccination because it’s cheaper than culling flocks.

Broiler producers oppose it because their birds live shorter lives and face less risk—and because vaccines could jeopardize exports, a big part of their business.

And even if the industry agreed on vaccines, logistics are a nightmare. Some farms house millions of birds. How do you vaccinate every one of them by hand? Labor shortages, worsened by immigration enforcement, make this even harder. Farmers want vaccines that could go into poultry water or feed, but they don’t exist yet, and manufacturers won’t develop them without guaranteed demand.

It's Not Just Chickens!

Though billed as a broad strategy, the plan is almost entirely focused on laying hens. What about turkeys and other poultry? What about dairy cattle and other mammals? What about wild birds? For example:

Dairy cows in 17 states are infected. While not often fatal, the virus lowers milk output and forces destruction of infected milk.

Pigs are particularly dangerous because they can host both human and bird flu viruses—allowing the viruses to swap genetic material and possibly create new, human-infecting strains.

Senator Amy Klobuchar, the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Agriculture and three other senators wrote a letter to Agriculture Secretary Rollins in April urging that the new initiative also include measures for turkeys and dairy herds. So far, there’s been no public response.

At the same time, funding for avian flu programs abroad and for wild bird surveillance in key migratory zones is being cut. These programs are essential for early warnings and global containment.

Ignoring a Root Cause: Factory Farms

One of the main reasons bird flu keeps spreading is the structure of modern poultry farming. Millions of animals are packed tightly together, creating ideal conditions for viruses to thrive and mutate. Yet the new USDA plan doesn’t address this at all—in fact, it may undermine efforts to fix it.

Take California’s Proposition 12, passed by voters in 2018. It bans cramped cages and requires more space per animal, even for products sold in California but produced elsewhere. The Supreme Court upheld it in 2023.

But Secretary Rollins opposes Prop 12. In her confirmation hearing, she said she’d work with Congress to overturn it. The USDA’s mention of “regulations and price hikes, especially in states like California,” is widely seen as code for rolling back Prop 12.

“Repealing state bans on cages won’t stop the spread of bird flu,” The Humane League’s Senior Policy Counsel Hannah Truxell stated in an interview with Vox. “It would, however, reverse years of critical food industry progress.” This prong is not just ineffective; it is counterproductive and dangerous.

And So….

At first glance, the USDA’s five-pronged plan looks like bold action. But on closer inspection, it’s mostly a repackaging of old programs, with limited scope, incomplete implementation plans, and little attention to the bigger picture. It focuses on laying hens while neglecting turkeys, cows, pigs, and wild birds. It promotes factory farms while threatening more humane practices like those in Prop 12. And it asks an understaffed system to do more with less.

Yes, vaccines are promising—but they’re not a magic fix. And ignoring the role of high-density, industrial animal farming is a major missed opportunity.

Will this five-pronged plan stop avian flu? Not likely—not in its current form. Five prongs don’t make a right.

When Will It All End?

Avian flu has become embedded in wild birds—it is endemic and it persists in all seasons, year-round. The herculean effort by state and federal government agencies to manage and control it in poultry and other domestic animals is not working as well as it used to and is now in a state of flux.

Right now, the threat to people is small—people can only get it from infected chickens, cows or other domestic and wild animals. That critical mutation that would allow the virus to spread human-to-human has not occurred.

When will it end? Perhaps never. This may be the new normal. So, all of us need to do all the things that are necessary and important for us to do in this situation. Stay informed. Stay safe. Protect our flocks. Speak out against bad public policy. While bird flu may never be eradicated, proficient monitoring, our precautions to protect ourselves and our flocks, and new innovations and research efforts can control it and curtail its effect.

In this brave new normal, all of us must do what we can to live our best lives. And we must do what we can do so our backyard chickens can live their best lives, too.

In this article I have used the terms “bird flu” and “avian flu” interchangeably. Both terms refer to the same disease and mean the same thing.

Flu: The Coop - Avian Influenza and Backyard Chickens

Part 1 - Two Viruses: Thoughts on Bird Flu and Covid

Part 3 - Can I Catch Bird Flu From My Chickens? Will it Cause the Next Pandemic?

Part 4 - Why Are Egg Prices So High? When Will They Return to Normal?

Part 6 - Bird Flu 2025 –Protect Your Backyard Flock – Protect Yourself